The Empire Gem

Torpedoed January 23, 1942

8,139

Gross Tons

463

feet 2inches Length, 61 feet 2inches Beam, 33feet 1inch Deep

Owner:

British Tanker Company of London

Builder:

Harland & Wolff, Ltd., Glasgow, Scotland

Depth

150 feet

History of the Ship

Empire Gem was

laid down as hull number 1045G at the Harland & Wolff yard in Glasgow,

Scotland and launched on May 29, 1941. The Harland & Wolff yard began constructing vessels in 1861 in

Ireland. By 1912 they had acquired a yard in Glasgow, Scotland and moved

the majority of their effort there, mainly due to growing political instability

in Ireland. In latter years the yard returned to operations in Belfast,

where they still conduct shipyard work today. The yard has constructed a

wide range of vessels, but are most famously know as the builder for all the

White Star Line vessels, to include the ill fated RMS Titanic.

Though built in the yard that produced the most elegant

luxury liners of the era, the Empire Gem was not a luxurious vessel, but a

workhorse designed to carry over ten thousand tons of oil products. She

was a Ocean Design tanker that was Diesel powered and could efficiently make

reasonable speed. The Ocean type tankers were sometimes known as the

'Three Twelves Type', being about 12,000 tons deadweight with a speed of around

12 knots and a fuel consumption of 12 tons per day. The Gem was under the

control of British Ministry of War Transport (British Tanker Co. London as the

managers) so the Gem was given the prefix name of "Empire", in keeping with the

British method of naming all the ships built or pressed into government service

for the war effort being prefixed as "Empire". When she sailed to

America to transport gasoline and oil products for the British war efforts, she

was basically a government ship being run by a private management company.

Sinking of the Ship

Francis Reginald Broad, the British master of the British tanker Empire

Gem, was a confident, self-assured man as his 8,139 ton vessel left Port

Arthur, Texas on January 18, 1942. He was proud of the cargo she was carrying

- 10,600 tons of gasoline for the Petroleum Pool Board. He was equally

proud of his all British crew, which he felt was thoroughly loyal and able

to deal with any of the hardships of war.

The Gem's full load was being transported from Port Arthur to the United

Kingdom by way of Halifax, NS, where she was to join a convoy and then cross the

Atlantic for England. Although she

hoped not to use them, the ship was equipped with guns for dealing with

any marauder. On her stern was a four- inch gun, and elsewhere were six

machine guns and a 12 pound anti-aircraft weapon. It was as well to have

them since the German submarines had commenced operations off the eastern

US coast.

The skipper followed the British Naval Control instructions closely as he zigzagged his course up the east coast. Broad took great care to

zigzag and to travel at night with dimmed masthead and side lights.

Less than a week earlier,

submarines had struck three times in the vicinity between Hatteras and

Wimble Shoals so as the Gem neared Cape Hatteras on the morning of January 23rd, the Captain

became more scrupulous in his cautious approach. Late that afternoon, the Gem sighted another merchant ship, the

Venore, who was also headed North.

As night fell, the Gem closed her distance to the Venore until she was

within three miles. Standing

on the bridge, the Captain was pleased to note the clear weather, with

excellent visibility. The moon shone so brightly that the Gem could have

proceeded without her lights but she turned on the running lights and the Venore could be seen in the distance

with her lights also shining brightly.

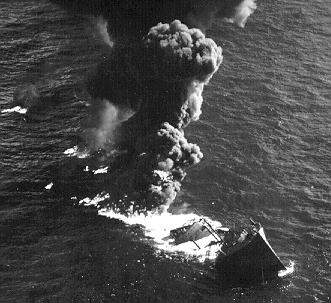

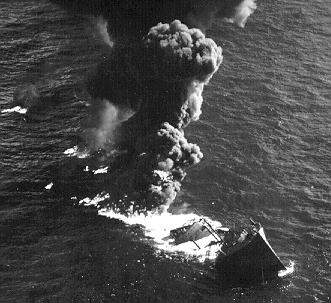

Unfortunately

for the Empire Gem, Korvettenkapitan

Zapp and his crew in the U-66, a type IX German Submarine, had arrived off Cape

Hatteras on the same day the Gem had sailed from Texas, January 18. Since

then, the U-66 had been working the area sinking vessels and once again the U-66

was about to show their skill and luck with

another expert attack, this time on a large tanker.

The Gem had reached a position 15 miles southeast of the Diamond Shoals

buoy when she was rocked by a terrific explosion in what the Captain judged

to be one of the after tanks on the starboard side. The damaged section was enveloped in roaring flames which were spreading rapidly.

The chief radio operator reached the bridge and tried to send a message

after the torpedo hit. At the same time he heard the Venore sending an

SOS. Throughout the calamity, the ship's engines were running, taking the

Gem on a westerly course. Three hours after the attack, the engines finally

stopped. Three officers (the only survivors of 57 men) anchored the still

burning vessel in 28 fathoms of water. As the dawn of the next day crept

over the horizon, the torn and gutted after half broke away and sank.

The chief radio operator reached the bridge and tried to send a message

after the torpedo hit. At the same time he heard the Venore sending an

SOS. Throughout the calamity, the ship's engines were running, taking the

Gem on a westerly course. Three hours after the attack, the engines finally

stopped. Three officers (the only survivors of 57 men) anchored the still

burning vessel in 28 fathoms of water. As the dawn of the next day crept

over the horizon, the torn and gutted after half broke away and sank.

Approximately three hours later, a Coast Guard lifeboat attempted to

rescue the three officers. Rescue was hampered by the flaming gasoline

and the high seas. The trio jumped into the sea to swim to the rescue boat.

However, Radio Operator Ernest McGraw was swept into the burning fuel by

the seas and perished.

It was not until later that the two survivors knew the fate of the Venore.

They had assumed that from the SOS received that the Venore had been attacked

first, when as a matter of fact the glow of the flaming Gem had illuminated

the Venore for Zapp's torpedo attack. The Venore had spotted the submarine

heading for her, and she sped away from the blazing tanker, but even with

evasive maneuvers she had been unable to outrun the sub and the Venore

joined the Gem adding two more vessels to Zapp's record (now totaling five

for this patrol).

Diving

the Gem

Today,

experienced divers will find the Gem (also known locally as the "smell

wreck") in two distinct sections that are in line with each other with

about 75 to 100 feet separating the two. Strangely, the stern section is rotated

180 degrees with the fantail facing the torn off bow section and the engine and

torn section facing away. The bow section is the largest portion

comprising about 2/3 of the wreck and lays completely upside-down.

Although

large and impressive to see, the bow offers nothing other than a large looming

hull bottom to inspect with some sparse scattered debris to either side.

The entire bow section is intact from the stem to where the hull was torn in

half just prior to the engine room. However,

it is completely upside down with both gunnels buried deep in the sand –

simply a huge encrusted hull bottom with nothing in the way of artifacts or

anything else of interest.

The

stern of the wreck is where to find the most exciting diving, as it is fairly

upright with many of the internal portions exposed through the collapsing decks.

The entire stern has a pronounced list to the starboard with a larger amount of

debris lying in the sand to the starboard side. The prop and rudder are

clearly visible as is the steering quadrant and many large deck fittings on the

fantail. Forward of the taffrail to the engine area is fairly intact with

some holes allowing access to the lower decks and machinery. On the port

side just aft of the engine are some areas that can be entered and explored, but

I have yet to find much of interest in these small compartments.

At

the engine room, the structure has fallen away exposing the large engines and

other equipment. The twin diesel engines are arranged not side by side,

but fore and aft on the centerline of the engine room. They are at least 8 to ten feet wide and the tops of the

engines have massive rocker arms that are a yard long.

About 25 feet forward of the engines the wreck ends abruptly where the two

sections where torn apart. This

exposes the remains of the torn away and collapsing decks descending to the sand

where a debris pile of torn metal and various fittings is found.

At

the engine room, the structure has fallen away exposing the large engines and

other equipment. The twin diesel engines are arranged not side by side,

but fore and aft on the centerline of the engine room. They are at least 8 to ten feet wide and the tops of the

engines have massive rocker arms that are a yard long.

About 25 feet forward of the engines the wreck ends abruptly where the two

sections where torn apart. This

exposes the remains of the torn away and collapsing decks descending to the sand

where a debris pile of torn metal and various fittings is found.

The

wheelhouse is found upside-down, just off the side of the wreck several yards

away. In the standard visibility

you will not be able to see from the main wreck to the wheelhouse. At the sand there is a scattered debris field and divers have

reported seeing portholes and other artifacts there. It will take many dives to see the whole stern section

clearly as visibility varies greatly with the current, which can be very strong

in this area and usually is. However, we have dived the Gem in conditions

with no current and over 100 feet of visibility and it is even more impressive in these

circumstances. One must watch their gauges as we have seen over 150' in

the wash areas and there are some deep holes out in the debris field to the

starboard side of the wreck as well. Time

seems to go quickly when diving the Gem maybe it's all the great artifacts and

big fish.

Come

see for yourself why the Gem truly is a "gem".

Take

a look at Paul

Hudy's Empire Gem Web Page for a few more underwater photos and additional

information.

DiveHatteras Home

Send mail to webmaster@divehatteras.com with

questions or comments about this web site.

Copyright © 2003 Dive Hatteras LLC

Last modified:

February 11, 2016

The chief radio operator reached the bridge and tried to send a message

after the torpedo hit. At the same time he heard the Venore sending an

SOS. Throughout the calamity, the ship's engines were running, taking the

Gem on a westerly course. Three hours after the attack, the engines finally

stopped. Three officers (the only survivors of 57 men) anchored the still

burning vessel in 28 fathoms of water. As the dawn of the next day crept

over the horizon, the torn and gutted after half broke away and sank.

The chief radio operator reached the bridge and tried to send a message

after the torpedo hit. At the same time he heard the Venore sending an

SOS. Throughout the calamity, the ship's engines were running, taking the

Gem on a westerly course. Three hours after the attack, the engines finally

stopped. Three officers (the only survivors of 57 men) anchored the still

burning vessel in 28 fathoms of water. As the dawn of the next day crept

over the horizon, the torn and gutted after half broke away and sank.